FULL BIOGRAPHY

Ailsa Dixon was born in 1932, the second of five children in a musical family. Her mother Pat Harrison was a music teacher (having trained in Geneva with Emile Jacques-Dalcroze), and later founder of the Little Missenden Festival. A more distant ancestor was the violinist and composer Felix Yaniewicz, whose double violin case (originally containing a Stradivarius and an Amati) survived in the family; his portrait (right) hung next to the piano in the cottage where she grew up. Ailsa played the piano and violin, joined the London Junior Orchestra, and took her LRAM on the piano.

Ailsa Dixon was born in 1932, the second of five children in a musical family. Her mother Pat Harrison was a music teacher (having trained in Geneva with Emile Jacques-Dalcroze), and later founder of the Little Missenden Festival. A more distant ancestor was the violinist and composer Felix Yaniewicz, whose double violin case (originally containing a Stradivarius and an Amati) survived in the family; his portrait (right) hung next to the piano in the cottage where she grew up. Ailsa played the piano and violin, joined the London Junior Orchestra, and took her LRAM on the piano.

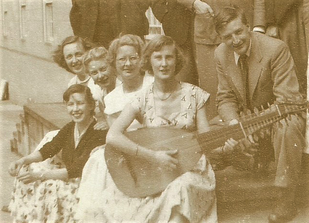

She read music at Durham University, where she was awarded the Kisch prize. It was here that her early enthusiasm for composition took wing, along with a burning desire to learn the lute which she later studied with Diana Poulton. After graduating she gave music appreciation classes for the WEA in London, taught the piano, and later became a singing teacher. With her husband Brian, she was a founder member of the Icknield Singers, a small early music vocal group performing Renaissance polyphony in the 1960s. Brian taught the classical guitar, and together they gave many recitals, focussing especially on lute songs from the Elizabethan period, and later also featuring some of Ailsa’s own compositions, notably the Songs of Faith and Joy.

In 1976, Ailsa and Brian produced Handel’s Theodora (then chiefly regarded as a dramatic oratorio) as an opera, staged in Aston Rowant church, with a cast featuring many of her singing pupils. In the wake of that project, she began to conceive an opera of her own, and wrote Letter to Philemon, which was produced in 1984. This was the beginning of a fertile period of composition, resulting in a number of vocal, instrumental and chamber works including three pieces for string quartet, developed under the tutelage of Paul Patterson (Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music). Her works have been performed by artists including Ian Partridge, Lynne Dawson, Cynthia Millar, Jacqueline Shave and the Brindisi Quartet.

Many of Ailsa’s works take inspiration from literary texts: vocal settings of Shakespeare sonnets, medieval Latin lyrics and Walter de la Mare’s poetry, and a piece for string quartet inspired by Matthew Arnold’s poem Sohrab and Rustum. Others reflect more spiritual sources of influence, derived from Biblical texts, hymns and prophetic poetry. Letter to Philemon, exploring an episode in the life of St Paul, draws on memories of early conversations with her grandfather, the Pauline scholar P.N. Harrison. One or two works are more abstract: Shining Cold is a wordless vocalise exploring the different sonorities of the soprano voice, the ondes martenot, and two stringed instruments.

Many of Ailsa’s works take inspiration from literary texts: vocal settings of Shakespeare sonnets, medieval Latin lyrics and Walter de la Mare’s poetry, and a piece for string quartet inspired by Matthew Arnold’s poem Sohrab and Rustum. Others reflect more spiritual sources of influence, derived from Biblical texts, hymns and prophetic poetry. Letter to Philemon, exploring an episode in the life of St Paul, draws on memories of early conversations with her grandfather, the Pauline scholar P.N. Harrison. One or two works are more abstract: Shining Cold is a wordless vocalise exploring the different sonorities of the soprano voice, the ondes martenot, and two stringed instruments.

Ailsa’s music frequently expresses a sense of the mysterious, but also features a sense of humour. Her strongest influences have come from the works of Fauré (for their harmonic suppleness), Britten (for his powers of evocation and empathy), and Bartok (whose compositional processes she studied in Durham, stimulating a special interest in lively variations of time signature and the elasticity of musical motifs).

In 2017, Ailsa’s anthem, These things shall be, setting verses by John Addington Symonds, was premiered by the London Oriana Choir, as part of the Five15 project, giving a voice to women composers across the UK.

Ailsa died in August 2017. A tribute to her life and music formed part of a remembrance concert by the London Oriana Choir in November, together with a performance of ‘These Things Shall Be’.

In 2017, Ailsa’s anthem, These things shall be, setting verses by John Addington Symonds, was premiered by the London Oriana Choir, as part of the Five15 project, giving a voice to women composers across the UK.

Ailsa died in August 2017. A tribute to her life and music formed part of a remembrance concert by the London Oriana Choir in November, together with a performance of ‘These Things Shall Be’.